Dr. Sarah Holtan talks to Drumm McNaughton, PhD

Continue readingMaximizing the Work of Boards

Dr. Sarah Holtan talks to Lawrence X. Taylor

Continue readingHigher Ed Efficiency, from an Engineer’s Perspective

Dr. Sarah Holtan talks to Andre Logan

Continue readingThe Cost of an Executive Search

Dr. Sarah Holtan talks to Scott Flanagan

Continue readingThe ROI of a Strong Brand

Dr. Sarah Holtan talks to Sarah Maio

Continue readingThe Savings of a la carte Student Services

Dr. Sarah Holtan talks to Dr. Steve Taylor

Continue readingFortifying the Ivory Tower

Dr. Sarah Holtan, the President and Founder of High-level Leadership, LLC

Continue readingAre the Great Resignation and Great Dropout Connected?

There’s nothing GREAT about employees leaving the workforce in the past couple years at higher levels than pre-pandemic rates (Yuan, 2022). There’s also nothing GREAT about students dropping out of college at higher rates than pre-pandemic rates (EDI, 2022). People are quitting, stopping out, saying: ENOUGH.

Do the Great Resignation and Great Dropout have anything in common? What might the commonalities tell us about how we work and educate now?

What is the Great Resignation?

The Great Resignation is sometimes called the “Big Quit,” and refers to the large number of attrition rates in US history, especially for employees in health care and technology (Yuan, 2022).

A 2022 MIT study cited the following reasons for employees leaving, in this order: toxic workplace culture; job insecurity and reorganization; the stress of highly-innovative companies; failure to recognize high-performers’ contributions; and poor responses to the pandemic. Interestingly, higher pay was not high on the list. It was number 16.

More female employees are resigning than male counterparts (Deloitte, 2022). And the exits may not be slowing down, at least in higher education. A third of student affairs practitioners plan to leave the field (Alonso, 2022).

What is the Great Dropout?

College students are leaving school before they complete their degrees, which is the worst scenario. Students have paid into the college system but will not see the workplace reward of a degree.

The students who dropped out early in the pandemic aren’t returning to school (EDI, 2022). Drop out rates are 20% higher for males than females (ThinkImpact, 2021). These drop-out rates are higher than predicted by the demographic cliff, which wasn’t supposed to hit until 2025.

What are the Similarities between Work Resignations and College Drop Outs?

Both stem from burnout.

Employees are burned out from stress, non-work responsibilities (e.g., child care, elder care), and a lack of work boundaries and flexibility. Deloitte’s Women @ Work report found that 53% of women surveyed say their stress levels are higher in 2022 than 2021 and that they feel burned out.

Students are burned out from virtual learning, financial debt, and mental health issues.

It’s all just too much, all at once. People need a release valve from the extreme external pressures faced during the past two years.

The release valve is opting out.

For students, those that dropped out have not returned.

For employees, some are looking for other employment at companies with strong cultures. Others might not return until reliable social supports are in place, such as child care.

The dropping-out behaviors could indicate an anti-organizational movement exacerbated by pandemic conditions. People don’t want to be held to the restrictions imposed by hierarchical organizations. People want more choices, flexibility, and control over what they do and how they do it. They are too burned out to conform to inflexible structures. Perhaps this anti-organizational movement also explains the rise in self-employment over the past couple years.

What Now?

What will be our societal response to the Great Resignation and the Great Dropout? How will the stopping-out behaviors affect societal and economic trends long term? How will hierarchical organizations adapt to this murky, shifting landscape?

Organizations, both within the workforce and higher ed, will likely be forced to evolve. Employees and students are asking for more options, flexibility, and control. The evolution feels painful right now for many. The pain point is the ambiguity inherent in the nature of forced changes. The workforce and higher ed can continue to resist the changes or find ways to adapt that meet organizational goals as well.

Deloitte. (2022). Women @ Work 2022: A Global Outlook.

Hanson, M. (2022). College Dropout Rates. Education Data Initiative (EDI).

Lederman, D. (May 4, 2022). Turnover, Burnout, and Demoralization in Higher Ed. Inside Higher Ed.

ThinkImpact. (2021). College Dropout Rates.

Yuan, L. (March 29, 2022). The Great Resignation Statistics. The Career Project.

Overcoming Resistance to Build Consensus on Your Team

Collaboration is the usual go-to tactic to achieve consensus within a team. But what happens when the collaborative process hits obstacles or stalls out? How can you navigate through the collaborative process to continue working toward consensus?

Four Steps to Creating Consensus

Consensus is a complicated negotiation among people, processes, and systems. Try these four steps to build consensus.

- Identify whether consensus is desirable. Ask yourself: Do you really want to do to the work to achieve true consensus? Or do you simply want the group to agree with you and help you execute the project? If the latter, then forget consensus. In the latter case, be transparent about what you want to do, how it will be executed, and why you aren’t seeking group input on it (e.g., time constraints). On the other hand, consensus is achievable when time is on your side, the input of the group is valuable to the final product, you want to create new learning on the existing processes and practices, and you believe any resistance could be damaging to the work product or future relationships.

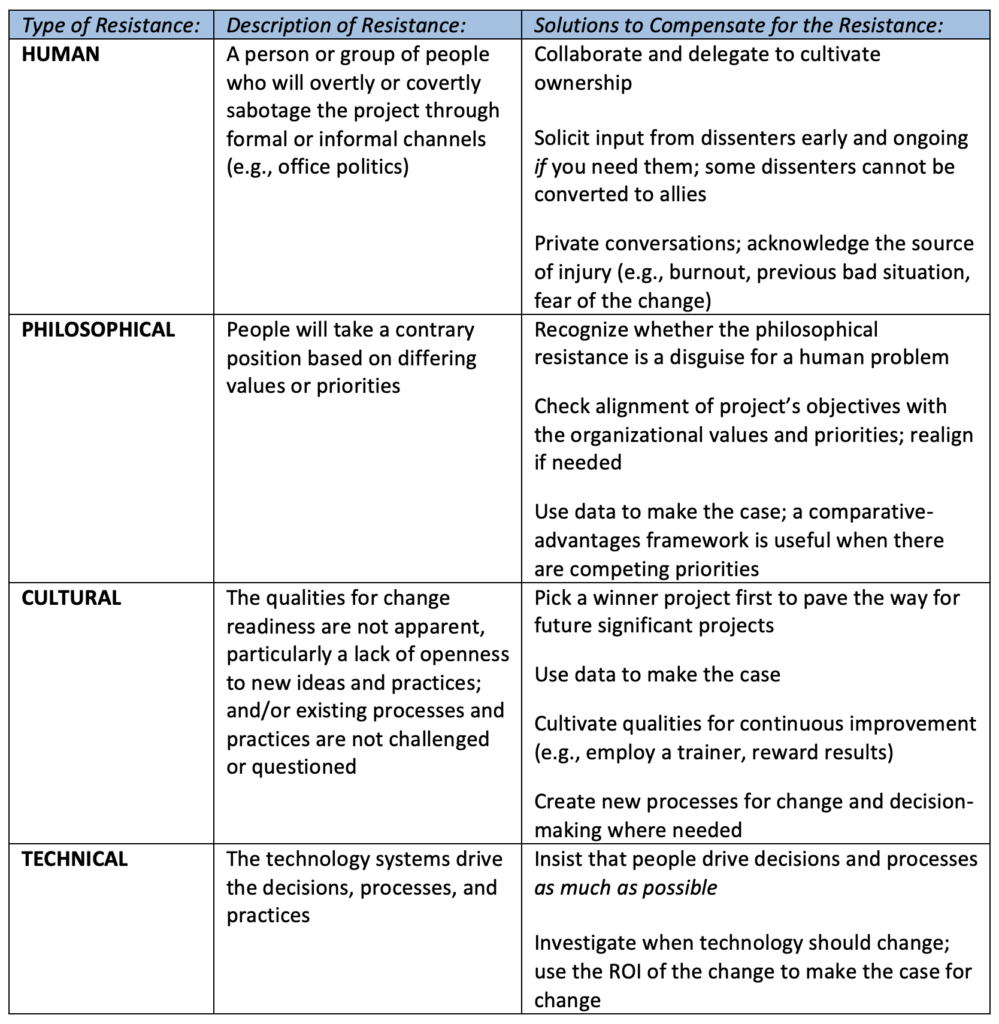

- Assess the resistance. It’s common to hit resistance during the consensus process. Most flavors of resistance can be classified as human, philosophical, cultural, or technical. See the table for details.

- Apply the tactics to overcome the resistance. Each type of resistance has compensation tactics to soften the resistance. See the table for details.

- Maintain the relationships. Congratulations – you’ve achieved consensus! But don’t undermine all the hard work to build consensus by blowing it now. You still need to nurture the relationships of the people who contributed. Otherwise, the collaborators will sense being used and you will become a “one-and-done” success story. Here are some ways to maintain the relationships, which will help create the conditions for consensus next time:

- Communicate regularly on updates and outcomes of the project;

- Demonstrate care, provide resources, and be accessible to the collaborators;

- Give credit wherever its due – remember, you didn’t get there alone;

- Celebrate victories; and

- Document and share the learning with the larger organization. When the project learning extends its reach, there is a sense of pride and ownership in contributing to the greater organizational good.

Beware of Groupthink!

Consensus is ideal but what happens when there is false consensus, and members of the team aren’t actually on board? This phenomenon is called groupthink, which is the illusion of consensus (Beebe and Masterson, 2012). Groupthink results from a dysfunctional absence of conflict or avoidance of conflict. The causes are a lack of group consideration of the advantages and disadvantages of the decision. You can see groupthink when actions are justified rather than evaluated, people are overconfident in the decisions, team members feel pressure to support decisions, decisions are made quickly, and team members prioritize the leader’s opinion over others.

To prevent groupthink, leaders can empower team members to question the merits of a project. Leaders should directly solicit the critical assessment of the team, especially the members who are naturally quiet. (Although tread carefully with team members who dislike being put on the spot.) Leaders can role model an evaluative model by questioning actions and decisions, especially their own.

References

Beebe and Masterson. (2012). Communicating in small groups. 10th Edition. Allyn and Bacon.